Stolen Generations

Stolen Generations—effects and consequences

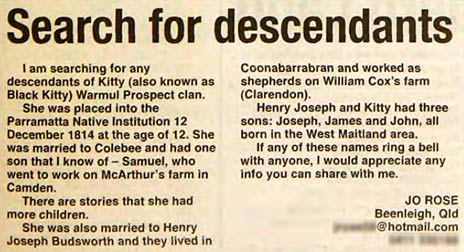

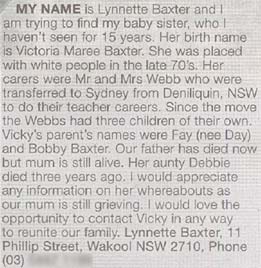

Removal affects all aspects of their lives. Some are still searching for their parents, others never succeeded as parents themselves and turned to substance abuse.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

Effects on those who were stolen

Members of the Stolen Generations often suffer from a range of problems.

Personal

- Low self esteem and feelings of worthlessness.

- Loss of identity. Carol Kendall's thoughts reflect both the positive and negative side of not being told one's identity: "When I was told I was Koori... I felt wonderful because this was the first information I had about who I was, me the real person, and I was Koori. I also felt frightened too because my skin was fair and I thought I wouldn't be accepted by other Koories." [2]

- Loneliness.

I have no identity really.

— Cynthia Sariago, daughter of a stolen woman [3]

- Mistrusting everyone. Aboriginal elder Prof Lowitja O'Donhoghue for example has a tendency to hold something of herself back from everyone but a selected few [4]. Having been brought up in an institution she never had a family in the traditional sense. Others became so paranoid that they didn't allow their family members to take food or gifts from people, because they thought these would be laced with poison, which actually happened when they were young. [5]

- Deep distrust of government, police and officials which continues to shape community relationships to these bodies.

- Internal guilt because Stolen Generation members often blame their mothers and fathers for not loving and caring for them, based on incorrect or sparse information supplied by foster parents and government institutions. Many ultimately find out that their parents never stopped trying to reunite with them. [6]

- Violence which can be domestic or intrinsic (leading to suicide). Mothers of the Stolen Generations living in remote areas are 3 times more likely to experience violence than other Aboriginal mothers. [7] They stay longer in violent relationships because they cannot bear their families being broken up again and their children growing up without a mother or a father. [1] Due to the limited focus on healing the relationship between Stolen Generations and their communities there is more lateral violence resulting in increasing isolation. [1]

43 of the 99 people whose deaths in custody were investigated in the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody had been separated from their natural families as children. [8]

Simon recounts...the time he first tasted alcohol, and how that, and later on harder drugs, worked to numb him of the blinding rage and violence he felt.

— Bill Simon, taken aged ten [9]

Relationships

- Unable to bond with family. For some, when they are reunited with a parent after many years (sometimes decades), the reunion turns into another perceived hurt and rejection when they find they cannot, or the parent does not want to, bond with them.

I met my mother for the first time when I was in my 30s, and it was sad because too much time had passed, and it was hard to make a connection.

— Aunty Maria Starsevik, taken aged two [6]

I didn't see my mother again until I was 35.

— Brian Morley, taken aged two [6]

Too much water had passed under the bridge. We became mother and daughter years too late.

— Elaine Randall [10]

Poem: The Search Begins

They had taken away my family! The child within me cried, The stolen life, the agony Of many a year gone by. The cover up; the pretence. The falsehood: All those lies. Didn't they know I'd find out the truth one day, And now I just ask WHY? All their words and all their kindness Can never fill the pain. Can I ever trust the people, That I believed in, once again? The stole me from a lifetime, My heritage. My home. My family. My identity. My spirit all alone. But to let them win, would be a sin. To give up would be a crime. I must search on. I must fight on. To find what is rightfully mine. To find my heritage; my family. My home and identity. To find the person who was lost to me. Me... the Aborigine!

Poem by Pauline McLeod. [2]

- Strangers to their family. Some siblings were put into the same institution without knowing the other kids were their siblings. They grew up to be strangers to their own family members, even later in life. [12]

- Difficulties parenting or filling any communal role. "As a child I had no mother's arms to hold me. No father to lead me into the world... We had few ideas about relationships. No-one showed us how to be lovers or parents." [13] They are unable to show love to their families and lost the ability to accept the love of their children, often because they are frightened to accept love. [1] Consequently many relationships of members of the Stolen Generations fail, dragging their children into a vicious cycle of foster parents. It is vital, therefore, to find family members for children in care or a new Stolen Generation grows up not knowing their parents. Afraid of being judged unfit parents, they are not seeking support for any of their problems. [1]

We never heard the words 'I love you', so we never learned to say them to our family... or feel them. We became empty vessels, out of touch with our feelings.

— Sharyn Egan, member of the Stolen Generations [14]

My mother did not bond with her mother and I did not bond with mine.

— Barbara Cummings, member of the Stolen Generations [15]

We kept coming across a pattern of Stolen Generation members whose children, then grandchildren and even their great-grandchildren had ended up in care.

— Glendra Stubbs, CEO Link-Up [16]

- Short family tree. Many Aboriginal people in rural and urban areas can't go further than two generations into their Aboriginal family tree. [17] Consequently they do not know which land they belong to; where to go to seek support for anything; they no longer belong to a community, hold no memories of belonging to one and are not able to draw on the strengths of a community to help them. [1]

A lot of us have lost our immediate family, so the girls from [children's home] Cootamundra are my family.

— Elaine Randall [10]

- Unable to manage relationships because they have never had a role model to learn from. Many relationships are violent and abusive (many abused become abusers).

He witnessed and suffered abuse that left emotional and physical scars so deep they would have a lasting impact on his life and all his relationships.

— Bill Simon, taken aged ten [9]

Economic

- Poorer education. Because they were brought up to be servants or labourers, members of the Stolen Generations often received a poorer education and are more likely to be unemployed. [1]

Law & justice

- No birth certificate. Aboriginal ex-footballer Sydney Jackson's "exact age cannot be guaranteed" because "no reference to the birth of Sydney Jackson can be found". His birthday was "simply assumed" to be July 1, 1944. [18] But people whose births were never registered or who do not have a birth certificate have problems applying for legal documents such as passports, cannot vote, legally drive, play sport, get a tax file number, enrol in school or access government support.

- Criminal offences which bring them to the attention of police and courts. In 1995, one in 10 Aboriginal people over 24 had been taken away from their families as children, and this group experienced far higher arrest rates. [19] A study found that 80% of Aboriginal prisoners in NSW were affected by the removal policies. [8]

Health

- Not visiting medical services. Aboriginal families expecting a child avoid seeking help to deliver their baby because they deeply distrust health services that continue to take children. "I still see families who don't come to services because they are terrified they won't get to take their baby home," says midwife Vanessa Smith, from the Woronora nation. Nurses and midwives had been integral to the policies that created the Stolen Generations. [20]

- Substance and alcohol abuse. "Most girls became depressed, suicidal and addicted to drugs and alcohol later in life," says Christina Green who was sent to the Parramatta Girls Home in 1970 for running away from her abusive foster parents. [21]

Our [bad] health is a legacy of our childhood.

— Christina Green, former Parramatta Girls Home inmate [21]

- Chronic pain. Trauma and difficult childhood experiences primes the nervous system to interpret danger which can become part of the reasons for chronic pain. Many who suffer chronic pain had stressful, adversarial childhoods.

- Lower life expectancy. The trauma of being stolen manifests in the many health conditions listed here, both mental and physical, and consequently to shorter lives.

- Depression and other mental illnesses. Members of the Stolen Generations have over double the rate of mental illness than other Aboriginal Australians. [1] Some have suppressed feelings of grief and anger for many decades.

- Dementia and Alzheimer's. Research found that Aboriginal people with high rates of childhood trauma, including those who were forcibly removed from their families, are nearly three times more likely to develop dementia, especially Alzheimer's disease, than others. [22]

Many boys were told that their mother or their father (quite often both) was dead, when in fact they were alive. Being told this news caused many to suffer severe depression... Some boys lost all hope and just wanted to die.

— Bill Simon, taken away aged 10 [23]

I was hurting and had found no way of safely healing the pain. So I turned the pain, anger, resentment and bitterness inwards and did what so many of us do, which is to punish and hurt ourselves. Despite being loved, I choose to suffer from days of depression and I couldn't see any hope in the future.

— Joy Makepeace, taken away aged less than a year old [24]

- Intergenerational traumas: Parents pass their traumas on to their children. "We need to recognise that the impact on the Stolen Generations has transferred from one generation to the next," says Richard Westen, CEO of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Foundation. [25] Families and children are impacted with "the same trauma, grief and loss".

A Western Australian child research survey showed "beyond doubt" the collective harm of being raised in a household affected by forcible removals. [26] 40% of Aboriginal children aged 0-18 are raised in a household where either a parent or a grandparent has been forcibly removed.

Removal affects even babies as Nikki Hartmann, manager of Post Adoption and Forced Adoption Services for Relationships Australia (SA), knows: "We know that babies feel that trauma. They have grown inside their mother. They know her smell, sound and movements, then they are taken away. The baby has experienced the first significant loss – also described as 'the primal wound'." [27]

We were part of an obliterated culture, just intact enough to know it exists, but so broken we didn’t think we could ever be put together again.

— Archie Roach, Aboriginal singer and songwriter, in his memoir Tell Me Why [28]

The fear I carry and the aversion I feel towards governmental departments is due entirely to inter-generational trauma. My mother carries this fear, my grandmother carried this fear, my great-grandmother carried this fear.

— Kelly Briggs, Aboriginal mother [29]

I know families who, if they see a stranger walk in their front yard, all run to the back of the house—grandmother, mother, son and grandson.

— Kim Hill, CEO Northern Land Council and former ATSIC Commissioner [30]

- Abuse which can be physical, emotional, sexual or of substances.

I was given the first hug of my life in a women's environment which I didn't know anything about... It tore me apart because not understanding what a hug is, and to be given that all of a sudden by someone, you suddenly realise someone cared about you, but it wasn't that. It was abuse, as a 12-year-old.

— Elder Mary Terszak, member of the Stolen Generations [31]

Spiritual

- Difficulties to find their religious beliefs, because often they have been brought to many different missions where they were exposed to various denominations. Others feel a strong indoctrination of the belief system they learned.

- Totems. Many traditionally oriented people don't know their totems which govern many aspects of their lives, for example whom they can marry.

I used to be so frightened of hell, or burning forever.

— Barbara Cummings, Aboriginal health worker and Stolen Generations member [15]

Cultural

- Loss of cultural affiliation. Since they were often denied any traditional knowledge, many Stolen Generations members find it difficult to take a role in the cultural and spiritual life of their Aboriginal communities. "I don't know nothing about my culture. I don't know nothing about the land and the language," says Cynthia Sariago whose mother passed away. "It's hard going back [to your home country] because you're not really accepted by your mother's traditional people." [3]

This is particularly true when someone who was removed has grown up overseas and taken on the accent of that country. "When she speaks it floors people to hear the different accents, and it's another barrier to reconnecting," says Gillian Brannigan, national co-ordinator for the National Stolen Generations Alliance. [33]

Sometimes this loss is a result of fear. "When Pop and Nan started having fair-skinned kids [because of a mixed relationship], the were worried because they were scarred by things that had happened during the stolen generations, so they moved off the missions," recalls Brooke Boney, a Gamilaroi woman from northern NSW. [34] In order to make life "easier" for their children, Brooke's Pop did not allow them to speak their Aboriginal language or practice culture and moved to a town where the population was majorly white. At the same time her Nan kept the house clean and the kids "pristine" for fear of government taking them.

I can remember when I was 16 and a big group of Aboriginals were walking towards me and I was terrified. I was green as grass. You had no knowledge of the outside world. All you was taught was house keeping.

— Iris Clayton, Stolen Generations member [2]

- Loss of language: "Many of us eventually lost our language... When some of us finally met our parents, it was almost impossible to bridge the language and culture gap.", says Uncle George Tongerie, who had been placed in Colebrook Home at Quorn, SA. [35]

Lee Nangala, 46, daughter of a member of the Stolen Generations recalls: "I remember saying over and over again to Mum, '...How come we don't have a language, Mum?... Mum, where do I come from?'" [36] - Loss of land. Not only can they sometimes not remember where their traditional land is, but in breaking the continuous practice of customs they are not entitled to claim native title over their land.

Many members of the Stolen Generations also had their wages stolen from them.

I suspect I'll carry these sorts of wounds 'til the day I die. I'd just like it not to be so intense, that's all.

— Bringing Them Home – Community Guide, the effects

Effects on family members who were not stolen

Some members of the Stolen Generations chose not to reveal to their families that they were stolen, hoping to spare them to find out what they went trough. [37]

Many parents, grandparents and family members never recovered from the distress of losing their children. Children who were not removed are still affected by the removal of their brothers and sisters.

Aunty Maureen Silleri has experienced this and can tell you best how it was like: [2]

Story: "My god you look like mum"

Maureen Silleri remembers what happened when her separated sisters and brothers came home.

"I was in about sixth class... and I came home and there was a young girl sitting in the chair. I walked in and looked at her and Mum said that's your sister. There was three of us left at home and six were taken away.

I sort of looked at her and thought 'my god, you look like Mum' and I kept staring at her thinking that she looked so much like Mum.

It was like I knew they existed and I knew they were around but to me they were strangers. So to me it was like getting to know them all over again."

When these siblings were talking about their experiences in institutions Maureen felt left out.

"I feel like they're on the inside and I'm on the outside. I know I can't experience what they have been through or have any idea of what it was like. I can't really relate to what happened back then."

Effects on birth parents

In hospitals it was often simply assumed by the staff that the baby would be taken from the mother soon after birth. No-one thought about what the birth mother or the birth father was feeling. [2]

Usually no encouragement or support was given to the birth mother to keep her child. On the contrary, mothers were forced to give up their child.

Many stories about the Stolen Generations are testimony to how very deeply mothers suffered because their children were forcibly taken from them.

Fathers took to alcohol after some, and sometimes all, of their children were taken because they had "nothing to live for". [12]

Some are unable to tell if their child was a boy or a girl, because a pillow was used as a barrier in the delivery room so that mothers could not even get a glimpse of their newborn child or make any form of maternal contact. [2]

The Pillow

They'd placed a pillow at my face to shield you from my view They didn't care nor realise that nothing they would do Could ever ease the pain I'd feel in ever losing you. A lifetime's passed, they've lied to me They promised I'd forget But as I lie awake at night A victim of their theft There's no-one I can turn to To help me in my plight Except... another pillow I weep into every night.

Poem by Di Wellfare. [2]

Birth fathers suffered too as they had often no say in what was to happen to their child.

They felt confused about the pregnancy, birth and relationship with the birth mother. [2] In many cases they had no opportunity to deal with their emotions or feelings.

Digression: Effects of removal on children's brains

The excellent book The Brain That Changes Itself explains what happens to a child which has been removed from their mother. [38]

"For children to know and regulate their emotions, and be socially connected, they need to experience [various kinds of emotional] interaction many hundreds of times in the critical period [of brain development] and then to have it reinforced later in life."

If a child is removed before or shortly after the critical period is completed other people need to take on the role of the mother. Stolen children rarely had others helping them to soothe themselves. They had to learn to "autoregulate" themselves by "turning off their emotions", a devastating blow to creating lasting relationships.

Children who grow up without their caring mothers, in institutions where one nurse is responsible for a group of infants, "stop developing intellectually, are unable to control their emotions, and instead rock endlessly back and forth, or make strange hand movements. They also enter 'turned-off' states and are indifferent to the world, unresponsive to people who try to hold and comfort them. In photographs these infants have a haunting, faraway look in their eyes." Compare this statement to the old newspaper photograph here. These children have given up all hope of finding their parents again.

Children suffering from early trauma release a stress hormone that kills cells in the hippocampus of the brain. This makes learning and long-term memory difficult and predisposes them to stress-related illnesses for the rest of their lives. "Trauma in infancy appears to lead to a supersensitisation" which can last into adulthood.

Growing up with ghosts

Children of parents who lost loved ones often 'grow up with ghosts', meaning that missing family members are psychologically present but physically absent [39]. While the parents know exactly whom they lost, their children know very little of this part of their family history.

Parents worsen this problem by hiding their traumatic memories, names or photographs. When they die they leave gaps in the family's history which can never be filled. "I didn't want to bother you with some of the crap I had to put up with," says for example the mother of Cathy Freeman [40]. Cathy is an Aboriginal Olympic gold medalist.

Aboriginal people are not the only ones suffering from such a loss of relatives and loss of past. Children of Holocaust survivors share the same experiences. [39]

I grew up knowing people 'I didn't know', mourning people I think were dead, but actually never knowing for sure.

— Child of a Holocaust survivor [39]

The children of survivors of great family losses find themselves left with many questions, shame and sometimes an almost obsessive desire to fill in the blank spaces of their family's past. This motivated Cathy Freeman in 2007 to sign up for a series aired by the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) television channel, 'Who do you think you are', and search for her heritage. [40]

"I wanted to know more about where I came from and who I belong to because one's history sets you on the right pathway for the future and makes you feel that bit more secure in the present," she explained.

I can see how I am a reflection of my ancestors.

— Cathy Freeman, Aboriginal Olympic gold medalist [40]

With this sentence Cathy explains how getting to know her ancestry helps her understand her own personality. Her search gives her a sense of purpose and helps her pass on a complete picture of her past to future generations: "It was important for me to know it so that I can share it with my children some day."

A relative or descendant of one of the four million Jews or political prisoners that Hitler exterminated in his death camps stands a better chance of learning the fate of his relatives than an Aboriginal person trying to piece together his or her family history.

— John Danalis in 'Riding The Black Cockatoo', comparing the extensive records Nazis kept about their victims to poor or non-existent records in Australia.

Other consequences

The forced removal of Aboriginal people also affects archaeologists and researchers today.

Birthplaces, family history and family trees – combined with film, audio and written records – are crucial for researchers to be able to map peoples' movements and reconstruct history.

But forced removal from their homelands or families scattered Aboriginal people all over Australia, making historical research on the connection between people and land almost impossible. [41]

Only if genetic information is present do researchers have a chance to establish movement patterns.