Health

Challenge: Eat healthy food in communities

Many Aboriginal meals are unhealthy because money is tight or community stores charge up to 3 times the price of food in cities. Solutions include licensing stores, making sure children eat their healthy food—or setting up a pool.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

Hunting for healthy food

As recent as the late 1950s, Aboriginal people in north-east Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, were living traditionally and enjoyed excellent health, with no chronic disease apparent. Twenty years later they were still renown for their self-sufficiency and optimal health. [3]

But assimilation into Western Australian culture drove them into a sedentary way of life and introduced smoking and refined foods. White flour, black tea and white sugar, first offered as rations and payment, became staples along with sugary drinks and other processed foods.

Historically, Aboriginal people's songs and dances used to contain clues about where to get food in the environment they were in, and rules of how to to hunt and cook. [4] Since then the hunt for food to survive has given way to the hunt for food that is healthy.

"In the past, my people did not know which new foods to accept and where to place them in our traditional food structures. This has resulted in much confusion around food, how it is processed, and it has resulted in people passing away too young," says Joanne Garnggulkpuy a Wangurri elder, experienced researcher and teacher. [4]

Particularly challenging is avoiding food that has been a childhood staple but is now considered harmful, such as damper.

We just eat the food from the store, and forget that we now have a choice of what we eat, a choice between healthy and unhealthy foods that have repercussions.

— Joanne Garnggulkpuy a Wangurri elder [4]

Aboriginal Australians' income is well below that of non-Aboriginal people. In 2012–13, Aboriginal adults earned on average only 53% of the gross weekly household income of their non-Aboriginal peers. [5]

Consequently, Aboriginal households either buy cheap (and unhealthy) food or run out of food before the next pay day. From October 2009 to October 2010, 15% of Victorian Aboriginal people had run out of food at some time [6] and nationally in 2019, 26% of Aboriginal people lived in a household which, in the previous 12 months, had run out of food and could not afford to buy more. In remote communities this percentage can be as high as 43%. [2]

Many find it easier to give their children money for fast foods, instead of cooking themselves, [7] encouraging them to make unhealthy choices.

Historically, Aboriginal genes are programmed to store fat in the body because food was scarce, especially in dry areas. "We have come from a desert country with genes that preserve everything we eat, but we are not burning the calories we once did in the hunt for food," explains Joan Winch, director of the Marr Mooditj (Good Hands) Aboriginal Health Worker's Training College. [7]

It's hard to avoid poverty in communities

If you happen to live in a remote community (only about a quarter of Aboriginal people do) you face another set of challenges.

Food prices can be more than triple the price of food in cities. Privately run stores tend to charge more than community run shops so that customers have to pay up to 70% more. A lack of competition is also a concern. A basket of basic dairy, non-perishables, and cooking supplies can cost $118 in the community but $85 at the supermarket in the nearest town. [2]

But the next supermarket can be an hour's drive and more away, so Aboriginal families buy food only once a fortnight or occasionally. They pick food they can keep in the freezer for convenience, which encourages unhealthy food choices.

Providing subsidised fresh fruits can greatly improve Aboriginal health. [9]

It is not a lack of food in communities which is the primary cause of food insecurity; it is a lack of money.

— Dr Francis Markham and Dr Sean Kerins, Centre for Aboriginal Economic policy research [2]

Video: The Distance Diet – challenges of getting fresh food in the bush

Helping people choose healthier options

Here are a few recipes that help Aboriginal people make healthier choices:

- Educate people. Many Aboriginal people are confused and do not understand what to eat because there is not much education [4] or they don't understand the labels. There is a need to learn how traditional food cycles, aligned with the seasons of the year, can deliver healthier choices.

- Encourage community. Community gardens, food shares and hunting and gathering of traditional foods are some things that can contribute to better health. [6]

- Help people prepare. Community cooking classes allow participants take home the meals they prepared so that families sit together to eat them.

- Blend traditional ways with contemporary knowledge.Hope for Health, a program developed in the NT, is based on Yolŋu traditional ways and healing methods and adds the best of non-Aboriginal modern nutrition. [4] It helps people master their own lives again and find a balance between both worlds.

- Make familiar foods healthier. Rather than banning foods Aboriginal people prefer, changing their ingredients bypasses the need to re-educate entire communities. For example, nutritionists worked with suppliers to improve white bread, the most popular bread on the APY Lands, which is usually low in fibre. Bakers developed a high-fibre variety that people in communities still enjoyed, without having to change habits. [10]

- Reduce sugar. Coca Cola claimed in 2008 that the Northern Territory was their highest selling region per capita in the world. Amata, a community of just 400 people, consumed 40,000 litres of soft drinks in 2007. This is because the way Aboriginal people get food has changed: In 1973 they bought only about 10% of supplies from their local store. Today it is almost 100%, partly because introduced plants have pushed out native grass that attracted animals for hunting.

Video: Mai Wiru (Good Food)

Why not support the Mai Wiru Foundation with a donation?

Bush tucker comeback

You might have heard about bush foods or 'bush tucker', an Australian expression for native food. Often associated with Aboriginal culture prior to invasion, bush tucker is increasingly seeing a comeback.

It is recognised for its healthy properties that help fight modern illnesses such as heart disease or diabetes, which is at crisis levels in Aboriginal communities.

Bush tucker food that is now used in kitchens includes fruit, nuts, wattle seeds, pepperleaf, lilly pilly, finger lime, bush tomatoes, strawberry eucalypt leaves and gum, riberry, warrigal greens, myrtles (lemon, cinnamon, anise), lemon aspen, quandong and sea-food besides the commonly known meats such as kangaroo, emu and crocodile.

Many native plants also have medicinal properties.

Everyone knows about Indigenous dance, art and the didgeridoo, but not about our food.

— Dale Chapman, owner-operator of Coolamon Food Creations [11]

There are more than 6,500 edible plants native to Australia.

Bush tucker challenges

This new bush tucker trend has its challenges. Aboriginal people harvesting the foods are often underpaid for the "gruelling work". [12]

In many minds 'bush tucker' evokes hunter-gatherer imagery but it has evolved far from that. Aboriginal chefs are now using methods any recognised Australian kitchen employs and show that Aboriginal cooking "is not out of place alongside Michelin-starred competition". [13]

Aboriginal people associate rituals and totems with bush foods, an important part when caring for and harvesting them. But non-Aboriginal farmers "don't have any idea about where the seeds have come from or what it actually means," complains Rayleen Brown, an Aboriginal woman who runs an Alice Springs catering company. [12]

Australian laws provide poor legal support for the rights of Aboriginal people to own, manage and develop their traditional resources. "There is a real danger in that we're starting to lose [produce] to the big corporates," says Aboriginal chef Mark Olive. "We're being restricted in accessing a lot of these herbs." [14]

While most Aboriginal land owners want to get involved with bush tucker there is a lack of Aboriginal providers. Aboriginal businesses make up less than 1% of the providers in the supply chain. [15]

Commercial growers easily circumvent Aboriginal property rights when they harvest bush foods grown on private land. Copyright laws do not protect Aboriginal recipes from being turned into food products. [12]

Story: The "Black Olive" chef

Mark Olive is an Aboriginal chef who has been working in the food business for more than 25 years. [16]

Early in his career he developed a strong desire to raise the profile of native Australian foods. His Melbourne-based catering company Black Olive Catering now showcases the best Australian native foods to national and international audiences.

He is hosting his own TV show The Outback Café where he shows his creative approach to food.

Other Aboriginal-owned businesses offering bush food include Coolamon Food Creations, Kallico Catering and Native Oz Cuisine.

Store licensing helps improve food quality

An independent report in 2011 found stores licensing in the Northern Territory has helped Aboriginal people in remote communities get better access to healthy, affordable food. [17]

During the second half of 2010, 86% of stores were selling at least 13 varieties of fresh vegetables and 91% sold at least 7 varieties of fresh fruit, the report found. In urban areas, the average grocery store carries 200 different kinds of fruits and vegetables. [18]

Store management had also improved, including financial management. Many customers appreciated that 'book-up' had been abolished and that there was now more consistent pricing and labeling of goods on shelves.

Problem: "Motorcar Dreaming" drains store profits

Store profits in some communities are not used to bring down prices, but instead finance cars for a chosen few, an administrative device called ''Motorcar Dreaming''. [19]

Spending store funds on vehicles seems permitted under Northern Territory legislation, provided the vehicles are designated for community rather than personal use--a constraint that is easily bypassed by assigning the cars to "family heads" and not documenting who owns which car.

Governments, both national and local, turn a blind eye on the phenomenon because it reduces their pressure to provide public transport to remote communities.

Problem: Book up

'Book up' is informal credit offered by stores. It allows people to get goods or services and pay the store later. Book up is also known as 'book down', 'on the tick' or 'on the slate'.

The system is easy to use, but also causes a few problems, such as too much debt, high fees or passive welfare dependency, and carries the risk of theft or fraud. [20]

Some communities therefore decided not to allow book up at all, or have limited its use.

A little control helps kids stay healthy

A stunningly simple recipe improved the children's health at Baryulgil Public School, 80km from Grafton, NSW. [21] Health officers discovered that all children were deficient in iron and vitamin C and had developed ear (50%) or skin (25%) infections as a consequence.

The simple remedy was fresh fruit and vegetables and a strict regimen to ensure they were eaten. Six months later the skin infections were gone and the hearing loss caused by the infection was drastically reduced.

Under a Shared Responsibility Agreement families contribute some dollars to the food packages which are now delivered to their communities. "Health problems are way down. The savings in health costs far outweigh the outlay for the scheme," says a campaign leader.

In 2018-19, 92% of Aboriginal children aged 2-3 years old ate an adequate amount of fruit per day and 23% an adequate amount of vegetables per day. [1]

You can only eat two of the more than 100 wattles, the black and green wattle seeds.

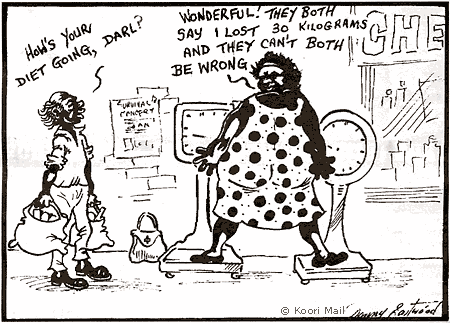

Obesity

Being overweight or obese is a serious problem that also affects many Aboriginal people. In one community, visits to a dietitian and diabetes educator accounted for about 27% of all visits. [22]

A survey in 2018-19 found that 71% of Aboriginal adults were either overweight or obese, 25% were in the normal weight range and 4% were underweight. Of the children aged 2-17 years, 38% were overweight or obese; 53% were normal weight and 9% were underweight. [1]

Further, 89% of Aboriginal people aged 15 years and over had not met physical activity guidelines, and 22% had not participated in any physical activity in the week prior to being surveyed. Aboriginal people in the ACT showed the highest level of activity (21%), the lowest was found in the NT (7.2%).

Targeting obesity and nutrition is a complex process, with many people suffering from more than one ailment, or weight gain combined with mental health issues, alcohol or drug addiction. [22]

Swimming pools boost more than just health

Another way to alleviate several common medical conditions is setting up a swimming pool. "Swimming pools are one of the simplest and most beneficial infrastructure initiatives that can be provided to Aboriginal communities," says Jay Weatherill when he was South Australian Affairs and Reconciliation Minister. [23]

People who use the pool avoid bronchial, skin and ear infections, the latter often leading to hearing and learning difficulties.

When a pool opened in the Aboriginal community of Jigalong, 350km south-east of Port Hedland, Western Australia, a subsequent 6-year study found that it had reduced middle-ear infections by 61% and skin infections by 68%. [24]

Pools are also a positive, fun and physical outlet for young people, taking them off the streets where they might be vulnerable to substance abuse and crime.

Some communities implement a 'no school, no pool' policy [23][24] and have seen significant improvements in school attendance.

A song about healthy traditional food

This is a song written by the students of Galiwink'u community school on Elcho Island, about 550 kms north-east of Darwin in north Australia, about the importance of eating traditional bush foods, hunting and living off the land.