Land

Native title issues & problems

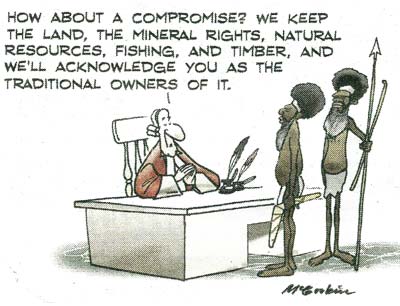

Native title parties need to prove an ongoing connection. Often numerous parties are involved. Processing applications can take many years which lets some politicians find strange "solutions".

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Native Title Act needs review

Native title legislation is not without issues. There are several problems which challenge native title parties and those involved in finding a solution.

The Native Title Act was originally handed down so that Aboriginal people could negotiate and mediate to resolve recognition of Aboriginal peoples' ongoing connection with their land.

But as more and more native title cases take many years, sometimes decades, to be resolved in courts rather than by negotiation, critics of the Act ask the Australian government to review and amend it.

The Act has caused division within Aboriginal communities because it's often misunderstood and mostly fails to include the Aboriginal perspective. It deals with Aboriginal people’s rights to land and waters but on 'white' terms that do little to advance Aboriginal rights. On the contrary, some Aboriginal people claim that it "denies Indigenous rights and is deeply embedded in Australian political institutions". [1]

"It's a whitefella legal construct," agrees Glen Kelly, a Noongar man heading the South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council in Western Australia. "What it is actually designed to do, in my view, is not to enliven traditional law and custom but to control traditional law and custom." [2]

One of the toughest requirements of the Act is that claimants have to be able to prove a continuity of traditional laws and customs on the land being claimed since European settlement.

Over time, many amendments have reduced the power native title could have. Judges and legislators have reduced native title to a tool with "little practical significance" because they either don't understand it or are actively against it. [3]

Native title is a weak form of title – it can be, and in many cases has been, ‘extinguished’ by all previous freeholding, by contemporary government action, or by ‘surrender’. It can only be claimed where other legal title (such as freehold) does not exist. And native title rights are typically non-exclusive, giving little opportunity to control access to land or its use. [1]

Native title is at the bottom of the hierarchy of Australian property rights.

— Tom Calma, former Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner [4]

Until we give back to the black man just a bit of land that was his and give it back without provisos, without strings to snatch it back, without anything but complete generosity of spirit in concession for the evil we have done him - until we do that, we shall remain what we have always been so far: a community of thieves.

— Xavier Herbert author of 'Poor Fellow My Country' (1970)

Video: Native title developments

Legal Special Counsel Robyn Glindemann in 2012 discussed the key developments in native title law since the Mabo decision.

Proving ongoing connection

Under the Native Title Act Aboriginal people have to prove their 'ongoing' connection to the land they want to claim native title for.

This ongoing connection is often difficult to prove, especially where there has been widespread urbanisation or agricultural development, both of which extinguish native title. Aboriginal wars with the white invaders, forced removal from their traditional lands (Stolen Generations) and many massacres of Aboriginal people exacerbate claims further.

The law requires a high level of evidence of each group's traditional connection which needs to go back to the date when the Crown asserted sovereignty over Australia [5]. Providing connection information is expensive and there is limited expertise available in Australia to develop these reports [5]. Connection reports can take 2 to 3 years to research and may take up to 3 years to be assessed.

During World War II Aboriginal people lost their ongoing connection around Darwin because they were evacuated from the Japanese bombing. "Judges haven't been able to take in account any mitigating circumstances, and that break is enough to throw the case out," says Tom Calma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner [6].

The doctrine of surviving title has some deep problems with it. It requires the Indigenous applicant to prove that colonisation did not hurt. The more it hurts, the less you get. The less it hurts the more you get. There is a deep contradiction in that idea.

— Chief Judge Joe Williams, New Zealand, commenting on native title in Australia [7]

Evidence used to prove Aboriginal people's connection to their land can sometimes date back over one hundred years, as exemplified in the Yorta Yorta people's native title case which used the 1881 petition of the Maloga residents to the Victorian government [8].

For the Gomeroi people's claim over areas in New South Wales computer mapping of family trees for 60,000 people, the largest known genealogy of Aboriginal people ever, along with hundreds of birth, death and marriage certificates demonstrated that the old way of life was still very much alive in Gomeroi country stretching from Singleton to Moree and out to Walgett [9].

The National Native Title Tribunal libraries can offer crucial evidence with their collection of rare and old books [10]. The Tribunal has offices in all major Australian capitals and offers personal assistance and email alerts.

However, cases exist where courts have denied recognising native title while at the same time acknowledging that the people before the court are the same people that owned that land at the time of colonisation [11].

Another problem is that, when a connection can be proven, the land is usually of low commercial value because it is remote from urban areas, which requires land owners to live away from mainstream work opportunities. Hence ongoing traditions, which are required to claim the land, and hold it, geographically disadvantage Aboriginal land holders.

As a consequence of extinguished native title the Indigenous Land Corporation was established to purchase land for groups who would not be able to prove native title.

During 2009 Tom Calma and Justice Robert French proposed to reverse the burden of proof in the native title claim system such that all claimants were presumed to have a "continuous existence and vitality since sovereignty" [6]. Former Prime Minister Paul Keating agrees, noting that "this onerous burden of proof has placed an unjust burden on those native title claimants who have suffered the most severe dispossession and social disruption." [12] A major 2015 report into Australia's human rights, compiled by nearly 200 NGO organisations around Australia, also demanded that "Australia should reverse the onus of proof for title to lands". [13]

Assuming continuous cultural traditions is a strong change to the process, says former Federal Court judge Ron Merkel. "The presumption of continuity is very powerful," he says. "Traditional law and customs do not spring up out of nowhere." [7]

Some judges, and I include myself amongst them, consider that the bar to successful proof of a native title claim is being placed too high.

— Justice Paul Finn [14]

Very limited negotiation time

With native title as complex as it is you would expect the legislation to allow plenty of time for parties to negotiate an outcome that serves both. But it doesn't.

It only gives traditional owners a six-month window in which they must negotiate with mining companies and come to an agreement. If they fail, mining can go ahead without any benefits to traditional owners. [15]

If new evidence appears after an agreement there is no way back – a flaw that led to the destruction of several sites, as new archaeological evidence could not be considered.

Governments bow to mining companies with compulsory acquisition and biased legislation

It can take decades for Aboriginal people to have their native title claims acknowledged, but it only takes a few days for their land to be compulsorily acquired by the government. Apart from time and tide, governments, it seems, also don't wait for anyone.

Australian governments are lobbied a lot by the resource industry and ever too willing to follow temptation, or money. Aboriginal rights to land come secondary.

In late 2010 the West Australian government served notice on traditional owners to compulsorily acquire land so that a commercial mining company could develop a processing plant for liquefied natural gas.

National Native Title Council Chief Executive Officer Brian Wyatt called on the federal government for help. "The action of the WA government in the Kimberley is sending a message to Aboriginal people that you don't have to negotiate in good faith and your rights are protected only when it suits the government," he said. [16]

In 2017, when Indian mining giant Adani planned to build Australia's largest open-cut mine in Queensland, not only wanted the government help the company with a $1 billion loan to fund a rail line, it also drafted legislation to bypass a potentially negative native title decision from a dispute the company was fighting in the federal court – with support from the opposition. [17]

"This [court case] is an issue for [t]his development but frankly it’s an issue for just about every development in Australia where native title issues are involved," Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said. "You’ve got to be able to reach agreements to get the development."

Stealing land from the Aborigines! I'd love to know how many times Australia has been stolen. Surely it must be the most stolen country in the world! And not just content with stolen land, they want to steal our children, our wages, our cultures, our identities, our ancient artefacts, our severed heads, our everything really.

— Phill Moncrieff, Aboriginal writer and musician [18]

Understanding the documents

How many times did you agree to terms & conditions without fully understanding them because you wanted to move on? What if I presented you with a legally binding document in a language that is not your mother tongue?

These are the challenges faced by Aboriginal people when they sign native title agreements, especially Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs). Michael Anderson, Convenor of Sovereign Union of First Nations and Peoples in Australia and and Head of State of the Euahlayi Peoples Republic, has analysed these agreements in detail. [19]

ILUAs are contracts, and some of them are lacking essential information. Some "have no commencement date and no end date, or, in the alternative, have a start date but no end date". Anderson calls these documents "sleezey, deceitful and fraudulent" because "there are open-ended indemnity clauses with no specification as to what the proponent parties are indemnified against" and clauses which seek consent for validating "all acts necessary to give effect to this agreement" without specifying which, or by listing agreements that have had no Aboriginal input in the past.

ILUA parties are required to agree that the Native Title claimants "…validate any invalid Agreed Acts done on the agreed Agreement Area prior to the Registration Date, to the extent that they are future acts", in other words, the wrongdoings of the past colonial era are now in the same category as future acts. "It is totally illegal to try and bind anyone to an unspecified future act," writes Anderson. "A future act would need to be defined in a statement to that effect in the ILUA itself and the claimants need to be made aware of this."

If Aboriginal people agree to an ILUA they also agree to "to permanently relinquish Native Title Rights and interests that may exist in relation to the Surrender Area" effective "immediately before a deed of grant is issued".

Anderson is sure that Aboriginal people do not understand the true nature of the consequences. "We can assume that in the vast majority of cases the ramifications and consequences have not been fully explained to our people by their lawyers," he says.

It is generally agreed in ILUAs that compensation arises, but, Anderson notes, it is generally followed by a statement in the ILUA which releases the state "from liability for any Claim and acknowledge that this Agreement may be pleaded as an absolute bar against any claims by the... [claimant parties]." Aboriginal people relinquish any further right or entitlement to compensation.

"How in the world can any of our people agree to something like this," Anderson asks. "Was the ILUA ever translated into the[ir] mother tongue?"

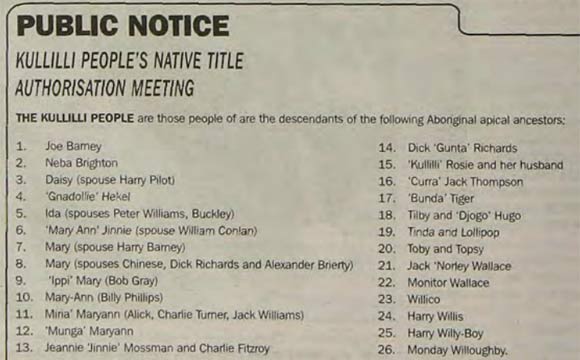

Numerous native title groups

For native title claims, parties can be numerous and diverse and their relationships complex. The Thalanyji people's claim in Western Australia involved more than 35 parties [20], the Gunditjmara people's case in Victoria involved hundreds of parties which were divided into 27 groups.

Besides the expected anthropologists, archaeologists, and lawyers, native title groups can include local, state and Commonwealth governments as well as representatives from the mining, pastoral, pearling, fishing, bee-keeping, telecommunications and many other industries.

The fact that these parties usually don't know, or interact with, each other complicates the mediation process. Parties might not have been in dispute with each other, but the native title claim brings them into a potential conflict. Claims can overlap with neighbouring claim areas, and any such disputes need to be resolved. About 45% of claims in 2008 had areas that overlapped with other claims [5].

Sometimes Aboriginal people who are not the rightful custodians for the claimed area sign away land and resources over which they do not have authority under traditional law and custom. [1]

If more than one Aboriginal group are claiming native title disagreements between Aboriginal groups can delay or even derail native title claims. One group might decide to lodge their own claim or disagree with the other group's decision, and claims might have to go back to the drawing board, taking many more years to be resolved.

Splits might also cause disagreements between families who have relatives on both sides [21], creating an environment for lateral violence.

If elders' views conflict with the agenda of others they might be deliberately excluded from native title deliberations [22].

Disagreements between Aboriginal parties sometimes split families "forever" [22]. Families who stuck by each other for generations are no longer on talking terms because of the conflict that has emanated from native title disputes.

In rare cases evidence found during research for a native title claim can lead to an Aboriginal group taking on a new identity[23]. This shows how ancestral knowledge got lost in the process of dispossession.

Little or no protection from mining companies

In some states or territories there is no requirement for a company exploring for resources to approach traditional Aboriginal owners directly if native title has not been determined for the area [25]. Hence local people sometimes know about the potential for minerals exploration from newspaper advertisements.

But even if native title exists it is no guarantee mining cannot start on the land.

In the Ward judgment of 2002 the High Court dismissed that native title constituted resource ownership (i.e. an "interest in land") and instead viewed it as a "bundle of rights" that, significantly, exclude valuable sub-surface minerals. The court reasoned that Aboriginal people "had not demonstrated laws and customs related to the use of minerals". [26] In a troubling way the court's decision confirmed that the Native Title Act allows "the piecemeal erosion of native title". [27]

As the online news site The Stringer put it [28]: "The Native Title Act is set up in such a way that both parties must enter into ‘good faith’ negotiations and hopefully come to a mutually beneficial deal within six months.

"If this fails you can count on the mining still going ahead. You can also count on the National Native Title Tribunal in granting the various licences required by the resource company and you can count on the Office of the Registrar of Aboriginal Corporations to stand idly by."

Mining companies have a book of tricks they try to convince traditional owners (TOs) to agree to mining [29]:

- Take TOs to the Native Title Tribunal to seek approval for the state to override their opposition.

- Pay for TOs to convene, including transport and food (which can be substantial, given the sometimes large number of groups involved).

- Organise their own meeting after that of the TOs in order to get people to agree to their Memorandum of Understanding to override any Indigenous Land Use Agreement.

- Excluding TOs that represent opposing groups from meetings, claiming they are "disruptive".

Lengthy process

Even if there is just one party making a claim and everyone acknowledges that they are the right people it is still difficult to settle claims and 'straightforward' claims can take a decade or more to reach an outcome [30].

Since both state and federal governments are involved in the native title process they wait for each other and exchange blame [31]. On average it takes 6 years to finalise a contested native title claim[11].

The first native title claim ever lodged (in 1994) was settled in November 2010 [32].

"One of the main reasons resolutions are delayed is the time it takes to prepare and assess the 'connection' material needed to show claimants' links to their traditional land or waters," says National Native Title Tribunal President Graeme Neate [33].

Even if a judgement by a single judge has been made it might not be the final word. In April 2008 the Full Court unanimously found that a judge had not applied the correct legal analysis in his interim decision. It sent the case back to a single judge for further hearing--almost 13 years after the first native title claim had been lodged [34].

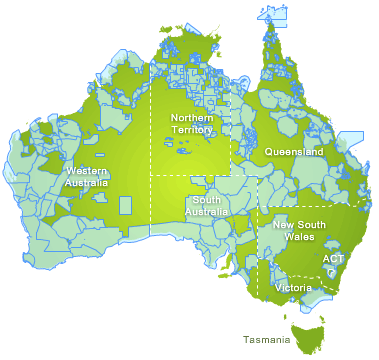

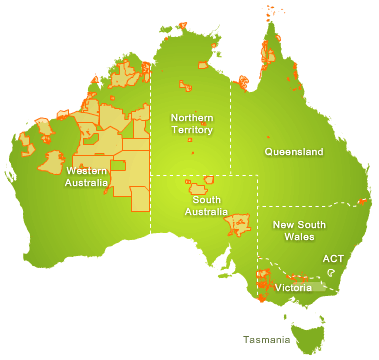

From 1993 to 2011 around 1,300 claims were lodged, but only 121 native title determinations resulted, covering just over 10% of the land mass at a cost to the taxpayer of over $900 million dollars [12].

Amongst the most vociferous [vigorous] opponents to native title are the governments. They're the ones who in part are responsible for the huge cost of it because they prolong the litigation.

— Prof. Mick Dodson, Aboriginal leader [35]

Compensation

Many Aboriginal people live on land rich in resources which will bring wealth for Australia, but delivers little for its Indigenous peoples.

A common misconception is that Aboriginal people receive millions of dollars "for nothing" just because mining companies set up camp on their land. Compensation is what the government owes Aboriginal people when it acquires an area of their traditional country, in a similar way as any private homeowner would be compensated if their property was compulsorily acquired for, say, a main road development [40].

Sometimes governments evade their responsibility to deliver basic services including health, housing and education in lieu of compensation payments which is wrong, says Indigenous Professor Marcia Langton [41].

"Compensation provisions have never been used successfully," says Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner Tom Calma [4]. The problem is that native title can easily be extinguished, it is impossible to 'revive' extinguished title, and there's a lack of either a right of veto or a statutory entitlement to any royalties from mining [42]. Private payments negotiated with mining companies allow these access to traditional lands.

Some mining companies believe that the Native Title Act aims to benefit all Aboriginal people, but this is not the case. It's only the traditional owners of that particular land who are entitled to compensation.

Mining companies are making millions of dollars profit each year operating on Aboriginal land. Between 1988 and 2008 it is estimated that the minerals industry has contributed some $500 billion into the Australian economy [43].

Companies are not required to pay a minimum return from their mining profits to Aboriginal people, and some mining companies pay as little as 0.25% of their gross revenue to traditional Aboriginal owners [36].

Up until 2019 there was little the Australian courts decided in terms of native title compensation. But in March 2019, the High Court finally confirmed compensation was due to native title holders at Timber Creek, NT. It was a landmark decision, thought to be as significant as the Mabo ruling itself.

There has not been one successful compensation claim.

— Tom Calma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner [44]

No trust in the process

During a native title process Aboriginal land councils negotiate with government.

Governments are unreliable

Governments base their negotiations on legislation, but they also have the power to change it to suit their interests.

After a native title claim was finally settled after many years of negotiations, the federal court found it to be invalid because some traditional custodians refused to approve the agreement. [45]

That prompted the Australian government to propose a hasty amendment to the Native Title Act (1993) to protect other agreements from appeal. The government wanted that agreements only needed majority support from native title holders to be valid, a move supported by the opposition.

Native title claimants have no protection against such spontaneous amendments to legislation which leads experts to consider native title law as a "minefield" and claimants being "at the whim of the legal system and changes of government and policy". [45]

Sometimes Aboriginal claimants wait years for governments to roll out changes their negotiated benefits rely upon, as is the case for the the Miriuwung-Gajerrong people who continue to wait after more than 10 years since their claim was successful.

Everything was delayed by a unilateral decision from the state government and they essentially left the traditional owners hanging.

— Michael Dockery, Curtin University associate professor [45]

People get disengaged

But many Aboriginal people do not trust these negotiations [46]. Sometimes "they have received so little coherent information about the offer and the negotiation process that they are... apathetic," says Aboriginal Elder John Pell of Western Australia [46]. "I venture to say that three quarters of the Noongar peoples no longer care and that 90 per cent of Noongars will not vote [on the native title case].”

Selective media reporting

Selective reporting in mainstream media adds to the confusion. Papers and broadcasters focus on the government’s position and supporters but fail to give enough voice to dissenters, probably because it takes more effort to get their voices.

Native title is discriminatory

Aboriginal Legal Service CEO and former NAIDOC person of the year, Dennis Eggington, says that "the claimant groups are made-up boundaries. Native title legislation bounds claims and the problem I have with that is that at an international level native title has been found to be discriminatory." [46] Land councils should not accept native title, according to Mr Eggington. But in the absence of anything better, Land Councils have little choice.

Financial issues

Native title monies paid to Aboriginal groups are eyed on by many parties—Aboriginal council members but also a plethora of lawyers and experts assisting the native title process.

No funding

The Native Title Act requires native title holders to establish a prescribed body corporate that represents them. But claimants have a disadvantage in negotiations because they do receive little or no formalised funding or support to operate as directors of a corporation, or deal with the complexities of financial and commercial law. [45][15]

"The burden is such that it prohibited [directors of native title corporations] holding any other job. You can’t work when this is taking up all your time and all of it is completely unpaid. You couldn’t imagine a similar situation in a white fella world," says Michael Dockery, associate professor at Curtin University. [45]

Up to 80% of funds lost to experts

Most of the resources for the historic Yorta Yorta native title claim (1994-2006) were "syphoned off by what became the bourgeoning 'native title industry'", a multitude of lawyers and experts who "quickly emerged from the Mabo decision, 1992". [47] Some lawyers charged up to $2,000 an hour. [3]

According to Dr Wayne Atkinson, Senior Fellow at the University of Melbourne, "only a small portion of the substantive funds allocated to assist native title holders in mounting their claims ever got to [them]". The majority, estimated to be "at least" 80 per cent, was paid to "members of the industry". [47]

You know what blackfellas right across this country use Mabo as an acronym for? Money Available, Barristers Only — because they’re the only ones benefitting from the system.

— Michael Anderson, Aboriginal lawyer [48]

Many involved in native title hold the view that those benefiting from the system may intentionally prolong native title proceedings rather than seek their resolution. [47]

Inner-council battles

No matter if Aboriginal groups received compensation or private payments, those payments might be a challenge to administer.

An Aboriginal council who received compensation payments has been reported to have "lost" a sum of more than A$500,000, bringing it to the edge of receivership. [38] Some of these monies were spent on inner-council battles over council membership as not everyone is admitted to the council and must prove that they are of that particular tribe's descent.

Few benefits from native title deals

Les Malezer, Chairperson of the Foundation for Aboriginal and Islander Research Action (FAIRA) in Brisbane, Queensland, criticises the native title system for its failure to deliver for Aboriginal people. [49]

"If Koiki Mabo were alive today he would be an angry man," says Mr Malezer. "The rights he won in the High Court have been eroded away by government, courts and socio-economic pressure."

"The current system has not achieved good outcomes in land rights. The native title debates have been so constrained that we have been left holding a process which does not work."

"It is a process that has been proven to be racially discriminatory, removed from the principles of land rights which has totally replaced the land rights agenda of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples."

The current legal arrangements in native title have the effect of obscuring the agents of dispossession and blaming the victims.

— Brian Wyatt, chair of the National Native Title Council [31]

An independent study found that only about 25% of native title agreements deliver "very substantial" outcomes for Aboriginal people, albeit with "enormous variations" [50]. About half of the agreements had only "little" benefits. All weaker agreements were negotiated under the Native Title Act and should not have been signed.

"Land-use agreements generally involve sacrifice of native title rights and heritage values supposedly in return for certain benefits," says Greens Senator Rachel Siewert [50], "however, where Aboriginal communities lack the capacity to negotiate these complex agreements or to ensure that they are enforced, they simply are not delivering."

Many of the people living under [the resources boom's] shadow continue to live in third world conditions.

— Rachel Siewert, Greens Senator [50]

Biased arbitration process

The arbitration process offered by the National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT) is flawed. The process is favouring mining companies and seriously disadvantages Aboriginal people.

Research shows that the Tribunal demanded more stringent standards of proof from Aboriginal groups than from companies [51], a problem that might be rooted in the Tribunal being government-appointed and not independent. Governments in Australia have great interest in supporting mining operations.

In 17 cases arbitrated by the NNTT under the Native Title Act, not one single mine was rejected. In 10 of the cases, no conditions were imposed on mining companies and only minimal conditions in the others [52].

The negotiating period for native title claims is 6 months. Companies know that at the end of a failed negotiation process they can go to the Tribunal and request that the mining lease be issued and the project go ahead regardless of Aboriginal stakeholders.

The NNTT is not permitted to consider awarding Aboriginal groups money towards the value of minerals taken from their land, which creates pressure on Aboriginal groups to reach an agreement outside of arbitration [51].

Indigenous interests are placed as secondary to the interests of mining activities, even when those activities have dubious economic benefits to the miner and the wider community.

— Paul Simmons, Senior Solicitor at Native Title Services Ltd, Victoria [51]

No veto rights

The Native Title Act contains no right of veto for Aboriginal people when mining companies intend to open mines on Aboriginal land, leaving them without benefits and a destroyed environment.

But a veto "is the only true test of whether it can be said that free, prior and informed consent has been given". [1] In fact, experts say free, prior and informed consent is not enshrined in the act. [15]

As a result, the incentive to reach an agreement is compelling and puts a lot of pressure on Aboriginal parties involved in negotiations.

"Leigh Creek mine, for example, has had an enormous detrimental effect on our culture," explains Vince Coulthard, Adnyamathanha, chairman of the Traditional Lands Association. [53] "They have dug up a very sacred site and made a huge environmental disaster and we have had no benefits at all from that mine."

"There's a lot of misinformation about this issue, but in reality Aboriginal people are very disempowered in this country and native title does not give us the right of veto of any mine."

As a result Aboriginal people have to go into negotiations to get the best possible outcomes, Vince says.

People occasionally draw adverse conclusions from claimants’ seeming willingness to ‘make deals’ with developers, but they have no choice. There is virtually no ability to stop a project.

Many agreements between mining companies and native title holders contain a "gag order" so that traditional owners cannot publicly object to any proposal by the mining company. In return mining companies promise to minimise damage. This order can act as a free ticket for the companies. The Banjima people, for example, were unable to object to an application to destroy up to 40 sites despite telling an archeological advisor they would “suffer spiritual and physical harm if they are destroyed”. [15]